I have been asked to produce effect size measures for a linear regression model. I do not like effect size measures but people who are a lot smarter than me do ask for them and they are often the peer reviewers who insist on them before you can get them published. I want to outline the debate about effect sizes and describe the variety of effect size measures that have been proposed for linear regression and analysis of variance.

Jacob Cohen and effect sizes

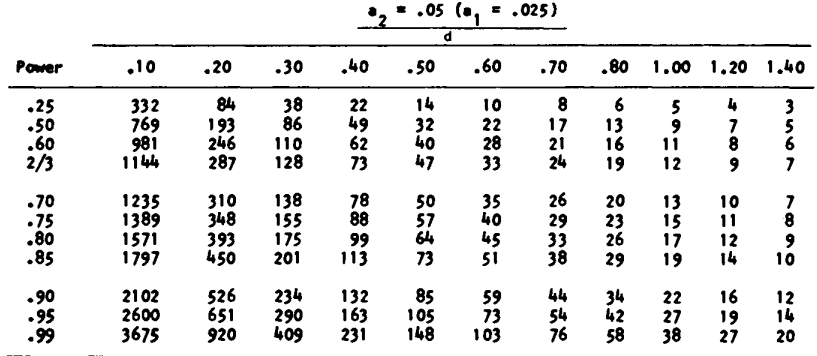

The effect size (ES) was popularized largely by Jacob Cohen in his 1988 book, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences with a second edition in 2013. This book has lots of tables that will tell you what sample size you need for your experiment. Those tables combine the ES with the desired power to determine an appropriate sample size.

Effect size for the two-sample t-test

The simplest ES is used in the two-sample t-test, where you test the hypothesis that the population average of one group differs from the population average of another group. This effect size is denoted by the letter d and is computed as

\(d=\frac{\mu_1-\mu_2}{\sigma}\)

where \(\mu_1\) and \(\mu_2\) are chosen to represent the minimum clinically important difference between the two groups and \(\sigma\) is the population standard deviation for the two populations. For the simplest case where there are the same number of patients in each group, you use a table like this one from Cohen’s book.

The effect size is a unitless quantity by necessity. You can’t have different tables when your outcome is measured in kilograms versus meters.

The big mistake

This is fine, but Jacob Cohen’s big mistake, in my opinion, was to advocate for the direct use of an ES when it was too difficult to specify \(\mu_1\), \(\mu_2\), and/or \(\sigma\). He reviewed the existing research and found a range of values for d where he substituted the sample means and sample standard deviation.

\(d=\frac{\bar{X}_1-\bar{X}_2}{S}\)

The bulk of the studies showed values of d from about 0.2 to 0.8. He then characterized d=0.2 as a “small effect size”, d=0.5 as a “medium effect size”, and d=0.8 as a “large effect size”. He then went on to speculate that certain disciplines were likely to see predominantly small ES and others might be fortunate enough that they could see large ES. Fortunate meaning that these disciplines could get away with using much smaller sample sizes. A large effect size means that you need a few dozen patients in each group to have reasonable power whereas a small effect size requires several hundred patients in each group for reasonable power.

Jacob Cohen then offers some ad hoc advice about effect sizes (page 13 of the second edition).

Many effects sought in personality, social, and clinical-psychological research are likely to be small effects as here defined, both because of the attenutation in validity of the measures employed and the subtlety of the issues frequently involved.

and

Large effects are frequently at issue in such fields as sociology, economics, and experimental and physiological psychology, fields characterized by the study of potent variables or the presence of good experimental control or both.

I find these comments to be overly broad. You cannot consign an entire discipline to the small end or the large end of effect sizes. Furthermore, you can’t judge clinical importance using a unitless quantity. I have a joke about this: A large store is having a sale and puts up a large banner bragging. All prices reduced by half a standard deviation.

Some critical commentary about effect sizes appears in Lenth (2001), an excellent article which, sadly, is behind a paywall. When you are planning a research study, you need to make choices that can separately influence the numerator (\(\mu_1=\mu_2\)) and the denominator (\(\sigma\)) of ES. If you consider only ES in your planning, you are conflating two very different features of the research.

In my opinion, you can only use ES as an intermediate calculation in power calculations. If you start planning a study with a statement like “We expect to see a medium effect size in this research” then you aren’t thinking clearly about the problem.

Post hoc effect sizes

It gets worse, however, than just sample size calculations. Many researchers have calculated effect sizes after their data is collected using sample statistics and then expound on the scientific merit of their research depending on whether the estimated effect size is small or large. A negative result (accepting the null hypothesis) with a large effect size is evidence that additional study with a larger sample size is warranted. The same negative result combined with a small effect size closes the door on further work. Large effect sizes can “salvage” an otherwise negative study. There are plenty of interpretations possible when you throw an effect size into the paper.

I feel that the only comparison that makes sense is looking at where the confidence interval lies relative to the range of clinical indifference. A confidence interval that lies entirely outside the range of clinical indifference is strong evidence of a definitive positive finding. A confidence interval that lies entirely inside the range of clinical indifference (even if the confidence interval itself implies statistical significance) is a definitive negative result and strong indication that further work is not needed.

Effect sizes in meta-analysis

Meta-analysis is the quantitative pooling of results from multiple research studies. Different researchers may use closely related measures of an outcome that are, unfortunately, defined in different units of measurement. You might see a mix of study on obesity where some measured change in weight, others measured change in body mass index, and still others measured change in percentage body fat. You can only combine these measures if you standardize them into unitless quantities.

The two most common methods to make the outcome measures unitless and therefore combinable are Cohen’s d (described above) and Hedge’s g. Hedge’s g is bias adjustment to Cohen’s d, and only important for small sample sizes.

When different studies use different outcome measures to assess the same thing, you should always ask whether you have too much heterogeneity in your meta-analysis. It is a judgement call, but sometimes you end up combining results that are too disparate. You may prefer to analyze subgroups with the same outcome rather than risk mixing apples and oranges.

Effect sizes for linear regression

Defining an effect size becomes a bit trickier for a linear regression model. I am including analysis of variance models in the umbrella of linear regression, but some researchers prefer to define separate effect measures for analysis of variance models.

Regression models with a single independent variable

The correlation coefficient is a unitless measure that you can cite as an effect size. In Chapter 3 of Jacob Cohen’s book, he defines a correlation of 0.1 as small, 0.3 as medium, and 0.5 as large.

You might report the effect size instead as \(r^2\). The obvious choice is 0.01 for small, 0.09 for medium, and 0.25 for large effect sizes.

Regression models with multiple independent variables

The statistic \(r^2\) defined above generalizes to

\(R^2=\frac{SS_{regression}}{SS_{total}}\)

or equivalently

\(R^2=\frac{SS_{regression}}{SS_{regression}+SS_{error}}\)

This is the square of the correlation between the observed data and the predicted values. It is not commonly used as a measure of effect size because it measures the aggregate predictive power of all of the independent variables combined. Instead, the partial \(R^2\) is often cited as a measure of effect size.

You estimate partial \(R^2\) by fitting a full model, one with every independent variable, and a reduced model, with every independent variable except the variable of interest. Partial \(R^2\) is a measure of how much less error that you have with the full model compared to the reduced model.

\(R_p^2=\frac{SS_{error}(reduced)-SS_{error}(full)}{SS_{error}(reduced)}\)

This measures the effect of an independent variable above and beyond the effects of the other independent variables.

Single factor analysis of variance

While you can fit an analysis of variance model using indicator variables and linear regression, many researchers prefer to consider these as a separate class.

A commonly cited measure is eta-squared (\(\eta^2\)). It is defined as

\(\eta^2=\frac{SS_{treatment}}{SS_{total}}\)

Equivalently, you can define this as

\(\eta^2=\frac{SS_{treatment}}{SS_{treatment}+SS_{error}}\)

Most sources point out that this is “analagous” to \(R^2\) in a multiple linear regression model. In fact, it is identical to \(R^2\), and it is a mystery to me why so many sources use the word “analagous.”

Multifactor analysis of variance

There is a partial \(\eta^2\) that is identical to the partial \(R^2\).

Note

I got the table excerpt from Jacob Cohen’s book from a source that has the text of the entire book. The full text of Jacob Cohen’s book on the web, all 579 pages. This is probably a copyright violation, but my excerpt of a small table for critical purposes probably falls under the fair use provisions of U.S. copyright law.

Bibliography

Jacob Cohen (2013). Statistical Power for the Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY. Available in PDF format.

Finnstats. How to perform Eta Squared in R. Finstats blog. Available in html format

Jim Frost. Effect Sizes in Statistics. Statistics By Jim blog. Available in html format.

Karen Grace-Martin. A comparison of effect size statistics. The Analysis Factor. Available in html format.

Karen Grace-Martin. How to calculate effect size statistics. The Analysis Factor. Available in html format.

Matthew B. Jané, Qinyu Xiao, Siu Kit Yeung, Mattan S. Ben-Shachar, Aaron R. Caldwell, Denis Cousineau, Daniel J. Dunleavy, Mahmoud Elsherif, Blair T. Johnson, David Moreau, Paul Riesthuis, Lukas Röseler, James Steele, Felipe F. Vieira, Mircea Zloteanu, Gilad Feldman. Guide to Effect Sizes and Confidence Intervals. Quartopub. Available in html format.

Russell V. Lenth (2001) Some Practical Guidelines for Effective Sample Size Determination. The American Statistician, 2001, 55(3), 187-193.

Wikipedia. Effect size. Available in html format